Gascoigne's Noble Arte of Venerie

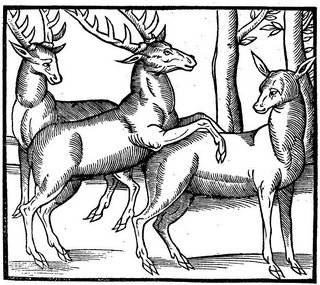

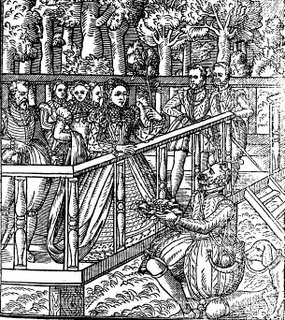

| After noticing how many people have arrived at our blog while searching for mostly unwebbed topics like "zombiism" and "Centlivre" (I think it's safe to say that Blogging the Renaissance is the only known place on earth where these two subjects sit side by side), I've decided to set up a few flaming beacons in the night for people who might be interested in the same useless early modern texts I'm interested in. So here's the first installment in a series I (and I hope my collaborators) will call EEBOnics. Well, maybe that won't be what it's called, but you get the idea. To kick things off, I thought I'd write a bit about the under-rated hunting text, The Noble Arte of Venerie (1575). First things first: it's not by George Turberville. EEBO makes this completely obvious, but since TNAV is often bound together with Turberville's hawking treatise, there's a loooong tradition of attributing it to Turberville, a tradition which has led to many a woodcut reproduction with the wrong name under it. The main body of the text is a translation of a French manual written by Jacques du Fouilloux, about whom I know nothing. But we all know something about the translator and expander of TNAV, George Gascoigne. What is there not to like about G.G.? Singlehandedly responsible for Englishing Italian comedy. Puts the plain into plain style. We say "a hundred," he says "A hundreth." That alone gets high marks in my book. To top it all off, he thought it would be an excellent idea to bring to the press a book featuring woodcuts like this one:  I love the little deer grins. They're happy! And why wouldn't they be? They're deer, trapped in a deer park, about to be chased in a restricted area by a pack of howling dogs, then shot at close range with cross-bows! Ok, ok, it wasn't always like that, but there's something very odd about the illustrations in TNAV. Such human eyes for all the animals, and such silly capes for all the humans. The book is essentially a hunter's guide to deer, fox, badger, hare, and otter behavior (thus the essential woodcut of deer sex), a hound-fanatic's guide to hound-raising  and a brief introduction to the complex mechanisms of the royal hunt. This last element has gotten the most attention from historians, for obvious reasons. The 1575 edition features several illustrations of Queen Elizabeth enjoying a day out in the forest as the central, controlling figure of a hunt (the 1611 edition sneaks James in for Elizabeth, although I get the sense that James didn't stand on ceremony when he hunted). Edward Berry has recently read these illustrations and the strange poems that come along with them as a kind of masque-like performance flattering the monarch, and in the context of TNAV, they certainly appear as such. But the props used in this masque deserve note. Take the following illustration:  Here's part of the poem that explains what's going on, lines spoken, ostensibly, by the huntsman kneeling before the Queen, trying to convince her that his deer -- as opposed to those championed by his competitors for royal favor -- is the one that should be hunted: For if you marke, his fewmets every poynt, You shall them finde, long, round, and well annoynt, Knottie and great, withouten prickes or eares, The moystnesses shewes, what venysone he beares. This all seems reasonable enough until you realize what the deer's "fewmets" are. The huntsman in the woodcut is actually holding them up to Elizabeth in a bed of leaves. Yup. Deer droppings. What I love about this (beyond the obvious) is its strange fantasy of royal power. Elizabeth is imagined here as an expert tracker of some sort, able to arbitrate between the competing claims of hunters, each of them holding a pile of droppings up to her and shouting, "Pick mine!" (I showed this image to a cynical friend of mine once, and he said, "Isn't this New Historicism in a nutshell? Showing crap to the Queen and telling her it means something?" Not quite right... but close.) In any case, I hope someone will write a monograph someday on hunting and early modern political power that puts the excrement and rutting at center stage. Berry, Manning, even E. P. Thompson... just not enough grit for me. Or for my main man G.G. [UPDATE: I decided to run a search for TNAV and discovered, shockingly, that this post is NOT the first item to appear. Check, among other things, this recent essay in EMLS for some actual thinking on the subject... even the fewmets.] |

At 4/21/2006 12:40:00 AM, La Lecturess wrote…

La Lecturess wrote…

Sheer genius. I've been laughing for the past five minutes straight.

At 4/21/2006 09:10:00 AM, Simplicius wrote…

Simplicius wrote…

"Fewmets"! Just think of the modern possibilities if this practice were revived (both symbolically and literally).

"Why did you choose that person and not me?" "Well, his fewmets were longer, rounder, and better annointed, to tell the truth."

"Why did she get a higher grade than I did?" "Honestly, she's smarter, but also her fewmets were knottie and great, withouten prickes or eares. The moistness of your fewmets, in contrast, was not apparent, and let's not even talk about the eares on them, sheesh."

At 4/21/2006 09:16:00 AM, Simplicius wrote…

Simplicius wrote…

I also love the grin on the voyeur buck. In fact, there's a small story to be told about the relationships among those three deer. Is it a tragic deer version of Troilus and Cressida? Or just some typically kinky deer sex?

At 4/21/2006 09:35:00 AM, Greenwit wrote…

Greenwit wrote…

The text accompanying that woodcut describes the "vaulting" practices of deer (see Hieronimo's Book of Sports post), and, specifically, the deference shown to older harts by the younger ones. There's a great passage about the deer sniffing the air before they vault, as if to "thank nature" for what they are about to do. Takes the pathetic fallacy to a totally new place. Thus the eyes, perhaps...

Scribble some marginalia

<< Main