Hugh Plat: Renaissance Man of Early Modern England

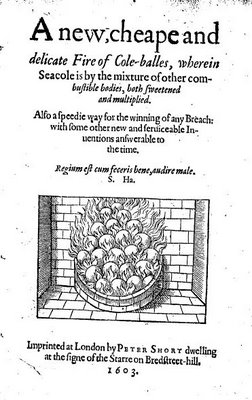

| I swore to myself long ago that I would never write a book about early modern husbandry manuals. I love them, but mostly for their frantic compilations of obviously terrible advice. Place horse hair on forehead for relief of scales; place horse hair under pillow for relief of unsettled dreams; drink bat broth to relieve obsession with horse hair, etc. Great stuff, but I’d hate to have to take it too seriously. And it is for that precise reason that I’m presenting this next installment in our EEBOnics series. I dedicate this one to all my homies in the soon-to-be-defunct microfilm departments in libraries all over the world. Keep those wheels spinning while you can, kids. It’ll all be over before the decade ends. No more fluttering clatter when careless rewinders lose track of time; no more cursing at illegible printouts of illegible reverse negative images… I’d call it bittersweet, but it’s hard to come up with the bitter side of things. I bring all this up because I first discovered husbandry manuals on microfilm reels while I was looking for other material. If anything is being lost with the switch to EEBO and other online archives, it is the ability to stumble across random proclamations and pamphlets on your way to item 12 on reel 433. I suppose abstract search terms might encourage a similar kind of accidental discovery, but it’s not quite the same as knowing that you’ve got one reel’s worth of strange new texts to read along with the ridiculously boring pirated catechism you’ve decided to track down. I also swore, by the way, a long time ago that I would never write a book about pirated catechisms… but that was a much easier oath to swallow. Back to the matter at hand. Historians of science and domesticity have shown us that before the middle of the 17th century in England, there was often very little dividing these two fields of knowledge. What we would now call physics, organic chemistry, engineering, cooking, medicine, biology, botany, veterinary arts, and brewing were all seen as essentially contiguous pursuits that fell under the categorical umbrella of husbandry. Of course, individual books on water-works and plant classification and chirurgerie were published in the sixteenth and earlier seventeenth centuries, and these kinds of divisions within the print marketplace no doubt played a part in the eventual (and in some ways unfortunate) conceptual divorce of chemistry from cooking, laboratory from home. But running against the grain of this trend were books like Hugh Plat’s The Jewell House of Art and Nature (1594), which includes the following in its table of contents:  This has got to be my favorite list of all time. How many people do you know today who can prevent drunkenness, steal bees, gather wasps, make a tallow candle last long, make parchment transparent, and make an excellent tent for a diamond? I would say Martha Stewart, but there is no way that woman knows how to steal bees. Sir Hugh Plat (knighted strictly for his ingenuity!) could do all this and more. He wasn’t really one for categorical organization, but as a figure in print, he sits at a truly early modern point of intersection between alchemy, housekeeping, engineering, botany, and pest control. And conceited drinking glass construction. This has got to be my favorite list of all time. How many people do you know today who can prevent drunkenness, steal bees, gather wasps, make a tallow candle last long, make parchment transparent, and make an excellent tent for a diamond? I would say Martha Stewart, but there is no way that woman knows how to steal bees. Sir Hugh Plat (knighted strictly for his ingenuity!) could do all this and more. He wasn’t really one for categorical organization, but as a figure in print, he sits at a truly early modern point of intersection between alchemy, housekeeping, engineering, botany, and pest control. And conceited drinking glass construction.Sir Hugh is mostly remembered now for his more focused contribution to the advice-manual genre, Delights for Ladies, which is essentially a cookbook with a few beauty tips thrown in for good measure (to whiten teeth, brush with horse hair!). But I’d like to draw your attention to one of his most obscure works, the title page of which appears below. Ladies and Gentlemen, I give you…  Cole-balls! Essentially, they were patties of sea coal mixed with loam that burned more sweetly and with less “smoot” than ordinary coal. Smootlessness is a big selling point here, since coal dust is, according to Sir Hugh, “a matter of so great offense to al the pleasant gardeins of Noblemen, Gentlemen, and Marchants of this most honorable Citie and the suburbs thereof, besides the discoloring and defacing of al the stately hangings and other rich furniture of their houses, as also of their costlie and gorgeous apparell” (B4v). Methinks the man beat John “Fumifugium” Evelyn to the air quality punch by around sixty years, but who (besides me) is counting? Not the vague internet authorities, I’ll tell you that much. Another cole-ball selling point seems to be fire aesthetics, and it is just like an Elizabethan inventor to care about such things. Cole-ball fire has a “forme and shape” which, Sir Hugh tells us, “doth far surpass all other fiers whatsoever; whose bals being round and all of one equall bignes, when they are all truly placed together, they do much resemble the piles of shot as they ly in a most beautifull manner within the tower of London” (C1r; I know for a fact the first time he reads this, Hieronimo will be snickering about balls of equal bigness). You might be able to tell from his odd decision to quantify beauty via mounds of cannonballs that Sir Hugh had a thing for munitions, and his cole ball treatise quickly wanders from its eponymous invention (“fit for a Ladies chamber”) into a few tantalizing hints about the devastating weapons he is beginning to invent. They are sadly prescient suggestions: an unmanned boat filled with explosives that sails on its own for half a mile, runs into another boat, then explodes; and a bullet that shatters into a hundred explosive fragments on impact. He also manages to fit in a few paragraphs on a wooden vessel that can be used to boil liquid (damning the Coppersmiths along the way for besmirching his character) and lets us know that he’s onto a way to triple the yield on an acre planted with corn. The man just has too much information to impart. In fact, it’s almost a little annoying how much he knows and how desperate he is to tell us all about it. Cole-balls! Essentially, they were patties of sea coal mixed with loam that burned more sweetly and with less “smoot” than ordinary coal. Smootlessness is a big selling point here, since coal dust is, according to Sir Hugh, “a matter of so great offense to al the pleasant gardeins of Noblemen, Gentlemen, and Marchants of this most honorable Citie and the suburbs thereof, besides the discoloring and defacing of al the stately hangings and other rich furniture of their houses, as also of their costlie and gorgeous apparell” (B4v). Methinks the man beat John “Fumifugium” Evelyn to the air quality punch by around sixty years, but who (besides me) is counting? Not the vague internet authorities, I’ll tell you that much. Another cole-ball selling point seems to be fire aesthetics, and it is just like an Elizabethan inventor to care about such things. Cole-ball fire has a “forme and shape” which, Sir Hugh tells us, “doth far surpass all other fiers whatsoever; whose bals being round and all of one equall bignes, when they are all truly placed together, they do much resemble the piles of shot as they ly in a most beautifull manner within the tower of London” (C1r; I know for a fact the first time he reads this, Hieronimo will be snickering about balls of equal bigness). You might be able to tell from his odd decision to quantify beauty via mounds of cannonballs that Sir Hugh had a thing for munitions, and his cole ball treatise quickly wanders from its eponymous invention (“fit for a Ladies chamber”) into a few tantalizing hints about the devastating weapons he is beginning to invent. They are sadly prescient suggestions: an unmanned boat filled with explosives that sails on its own for half a mile, runs into another boat, then explodes; and a bullet that shatters into a hundred explosive fragments on impact. He also manages to fit in a few paragraphs on a wooden vessel that can be used to boil liquid (damning the Coppersmiths along the way for besmirching his character) and lets us know that he’s onto a way to triple the yield on an acre planted with corn. The man just has too much information to impart. In fact, it’s almost a little annoying how much he knows and how desperate he is to tell us all about it.Hmmmm… A know-it-all pyromaniac with an inferiority complex who’s constantly trying to impress people by going on and on about his cool inventions? I think we’ve come across another candidate for early modern nerd. I would be less sure Sir Hugh deserves the label if it weren’t for this passage at the end of the cole balls book, a passage dripping with nerdly jock envy: I dare boldly conclude that the most valiant armie of the best approved soldiers, (yea though consisting of lovers themselves, and that giving battaile in the presence of their Ladies and Mistresses) may easily even with a small band of ingenious scholars and Artists be utterly overthrown and vanquished (D3v).Sir Hugh, I sincerely hope you’re eventually right about that one. |

At 6/03/2006 07:24:00 PM, Simplicius wrote…

Simplicius wrote…

"Rubbers for the teeth"!

Anyone familiar with "noisome vaults" and they might cause "offence"?

At 6/03/2006 08:07:00 PM, Hieronimo wrote…

Hieronimo wrote…

I imagine "vault" here refers to the underground vaulted chambers often used as storerooms in the cellars of buildings; they might become noisome because of all the cured meat, preserves, etc.--all those smells and all the possibilities for rotting.

That's my guess--I've certainly never actually read the text.

At 6/03/2006 08:30:00 PM, Simplicius wrote…

Simplicius wrote…

Apparently, "vault" was also slang for "a necessary-house," i.e., "a privy" (OED, n1, 4c). The first such usage listed by the OED is from 1617, and anyway, I'm sure Plat had storerooms more in mind.

Here's his actual advice: "Make the vent thereof vpward as large or larger then the tunnell downward, and carry the same vp to a conuenient heigth, for so the offensiue ayre as fast as it riseth hath issue and stayeth not in the passage" (sig. M1v).

Hugh Plat, Master of Ventilation.

At 6/03/2006 11:39:00 PM, bdh wrote…

bdh wrote…

*ahem* SIR Hugh Plat, Master of Ventilation.

At 6/08/2006 02:30:00 AM, Pamphilia wrote…

Pamphilia wrote…

Plat: Definitely a nerd candidate. Along with all the other 'books of secret writers' (cf. Thomas Eamon). Other Renaissance nerd candidates I'd like to propose: Harington and Puttenham (do not forget Harington's "Metamorphosis of Ajax"-- I know someone who wrote his entire dissertation on it. At least I think he did).

At 6/11/2006 03:49:00 AM, Pamphilia wrote…

Pamphilia wrote…

PS Harington, being the first credited early modern inventor of the flush-toilet, brings vaults to new, erm, "heights" with his classical parody, "The Metamorphosis of Ajax" (literally, "The Metamorphosis of a jakes

And Puttenham just has to qualify. His ode to Sir Andrew Flamock's musical rear end aside (which I think puts him more in the category of "early modern geek" or "early modern bathroom jokester"), and even his repeated use of inkhorn terms, he has to get points for never being able to make up his mind:

"But now because out maker or Poet is to play many parts and not one alone, . . . it is not altogether with him as with the crafts man, or altogether otherwise then with the crafts man . . .He is like the Carpenter or Ioyner, . . . he is as the painter or keruer that worke by imitation and representation in a forrein subject. . .But . . . he is not as the painter to counterfaite the naturall by the like effects and not the same, nor as the gardiner aiding nature to worke both the same and the like, nor as the Carpenter to worke effectes vtterly vnlike, but even as nature her selfe."

Geez, GP, make up your mind! You are such a total early modern nerd.

At 6/11/2006 04:05:00 PM, Greenwit wrote…

Greenwit wrote…

lov'n the puttenham...

At 9/07/2011 02:16:00 PM, Greenwit wrote…

Greenwit wrote…

You know, I haven't looked at this post for years, but I've read a good deal more on the history of science since I wrote it, and, since this will outlast anything I ever do in print, I suppose I should amend something above. There was an increasing amount of differentiation when Plat was writing between what we now think of as hard science and husbandry. I'm a bit too flip about that above. The much sterner me, five years later, disapproves. I wag a finger at you, younger me.

Scribble some marginalia

<< Main